How can the tech and green sectors work together?

Let’s all face it – there’s a clock, and it’s ticking down the seconds until we run out of the lifeblood of all tech – rare earth metals.

The problem with batteries

If you’re using anything other than a desktop computer that remains plugged into a wall socket, that device uses a battery for energy storage, which is – almost invariably – made of lithium (and other materials). Un-surprisingly, as a rare earth metal, lithium isn’t plentiful or renewable, and its reserves, just like any finite resource, will eventually deplete.

Some investors and analysts aren’t worried, as even if lithium battery production triples, there’s still 185 years of the resource scattered around the globe, just waiting to be mined.

Those concentrations of lithium are, however, often located in pristine wilderness like the English countryside or buried under land that belongs to indigenous peoples; over half of the world’s lithium reserves reside along the border of Chile and Argentina, home to herders who live on the Atacama Plateau, a land they consider sacred. The people of the Atacama Plateau are concerned about the water shortages and pollution that invariably comes along with mining operations – not to mention the inescapable geological scarring to their land.

Even if the ethical and environmental concerns aren’t worrisome for the tech sector, that number of 185 years should be. This projective estimate is based on a mere tripling of lithium usage for batteries – which is also used in the production of a lot of other materials; over one third of mined lithium goes to the fabrication of ceramics.

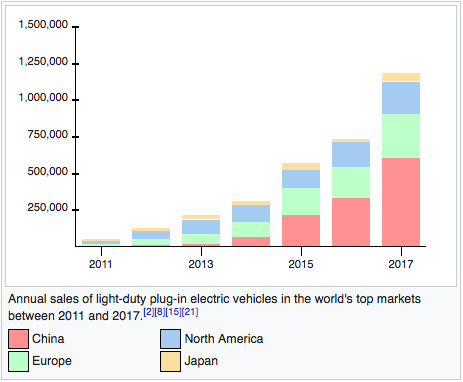

To make things worse, this isn’t just about smartphone, tablet, and laptop batteries – as the EV market expands, the estimated time that reserves will linger shoots way down. If there were 100 Tesla Gigafactories, we’d have enough reserves of Lithium to last 50 years. That many EV factories isn’t a stretch of the imagination – in 2015, 565,000 EVS were sold globally. In 2018, 2,018,247 million EVs were sold across the world – and that’s just passenger vehicles. That’s a market share increase from 0.38% (2014) to 2.1% (2018) in just four years.

As you can see above, this chart from Wikipedia shows annual sales of EVs are following the trend of exponential growth. As the auto industries in China and India begin to expand, this growth will only increase – and rapidly.

Still, many market analysts aren’t concerned; as this article on Bloomberg states, even if the cost of lithium were to increase by 300%, the price of a battery pack would only rise by a meager 2%. But this isn’t the real issue – no matter how economically feasible lithium remains, it’s still a finite resource. Earth is, after all, a closed system (other than a stray meteorite every once and a while) and while lithium is found in the ground, that doesn’t mean it grows there.

And what happens as the solar sector increases? In 2010, 0.1% of the United States’ energy production (which has been slow to adopt solar technology when compared to other countries) came from solar – that percentage has grown to 2% in 2018. For the past five years, solar has either come in first or second place for the winner of most installed type of energy production in the U.S., and even with current tariffs, is continuing its trend of rapid growth.

All of this energy produced by solar cells has to be stored somewhere – batteries. Wind power faces the same struggles with long term energy storage as well.

Last but not least, for the second time in as many weeks, we’ve got to talk about robots. It may be a few years off, but the robot revolution is coming – Spotmini (I swear I’m not on Boston Dynamic’s payroll, I just love this little guy) is projected to come to market this year.

Now I, along with everyone else who is old enough to have been self-aware in 2002, remember the promise of the Roomba; it was supposed to change vacuuming forever. And it didn’t. But the robots being developed now aren’t automated vacuums – they do their own stunts, act as fish-mimicking marine biologists, and can open doors.

Remember when the iPhone first came out? Sure, people thought it was cool, but we already had Mp3s and cellphones. A lot of people didn’t want this new-fangled “smartphone” – they were expensive, and the iPhone wasn’t capable of doing anything any other combination of laptop, cellphone, and Mp3 couldn’t. No one could have expected this device to produce its own industry and boost so many others.

Let’s go back – way back – to Times Square, ca. 1905.

Photo from Library of Congress

Horses and buggies everywhere. Next, let’s look at the same place just six years later, in 1911:

Photo from Library of Congress

There might be a horse in that photo somewhere, but there are a bunch of cars. The iPhone was released in 2007, and by 2013 – the same amount of time that passed between those two photos of Times Square – smartphones had flooded the market. Now, just as it’s practically impossible to get around the U.S. without a car, it’s difficult to stay up to date and function professionally without a smartphone.

Once a few trend setters start showing off their Spotminis fetching items, holding open doors while they carry in groceries, or even just following them around like their very own robot dog, you can bet people will follow suit. Envy is a powerful emotion, and a widely used sales tactic due to its power over our psychology.

Who doesn’t want to feel like Jeff Bezos?

So, the point is; soon, batteries (and the lithium that they are made with) won’t just be limited to laptops, tablets, smartphones, wearables, cars, and wind and solar energy. Robots will probably (definitely) have a huge impact on lithium’s demand.

It doesn’t matter if the price of lithium only goes up by 2% – at some point, in the not-so-distant future, we’re going to run out of the stuff.

So what are we going to do?

I don’t know, I just work here – but some very smart people are working on solutions.

- Researchers have figured out a way to not only capture CO2, but sequester it and the fabricate the carbon into electrodes.

- Alphabet owned, Cambridge-based Malta has made a heat pump that uses molten salt and antifreeze to store energy, and then convert it back into energy using a heat engine – this could store energy for weeks.

- Numerous companies are searching for a new form of battery – flow batteries. These use electrochemical processes to store a charge.

There’s still a lot of ground to cover, and many bridges to cross. Hopefully, as the tech sector moves into the 2020’s, it can evolve to meet the needs of both users and the earth.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!